When I first arrived at the Otago Museum (now Tūhura Otago Museum) in 2013, newly minted as its Director and fresh off the plane from England, I felt like a kid in a candy shop—or, more accurately, a history nerd in a room full of shipwreck relics. Among the museum’s treasures, a cluster of objects caught my eye: nails, a ballast stone, and a copper pintle and gudgeon—bits of HMS Bounty. Yes, the Bounty of mutiny fame, complete with Captain Bligh, breadfruit plants, and Fletcher Christian’s infamous coup. Naturally, I thought, “Why on earth are pieces of this historic ship in a museum in Dunedin?” My second thought was, “What the hell is a pintle?”

Objects from HMS Bounty on display in the Otago Museum’s Pacific Cultures Gallery

Fast forward to now: I know a pintle is a ship rudder’s hinge and that this one is particularly special because it survived not only the mutiny but also the 18th-century version of “if we burn the ship, no one can prove we did it.” This was just the kind of history I wanted to dive into, but life (read: moving jobs, countries, and entire hemispheres) got in the way.

Cut to late 2013, when the then British High Commissioner to New Zealand, Vicki Treadell, visited the museum. Being a dutiful host, I prepared by researching her many titles and stumbled on an unexpected gem: she’s also Governor of the Pitcairn Islands, where Fletcher Christian and company famously ended up. Bingo. I decided to show her the Bounty relics and a giant Moai (stone statue) from Pitcairn in our collection.

Moai from Pitcairn Island on display at Tūhura Otago Museum

Vicki seemed impressed until she asked, “Why do you have these objects?” Cue my blank stare. “Excellent question,” I mumbled while mentally noting to dig deeper.

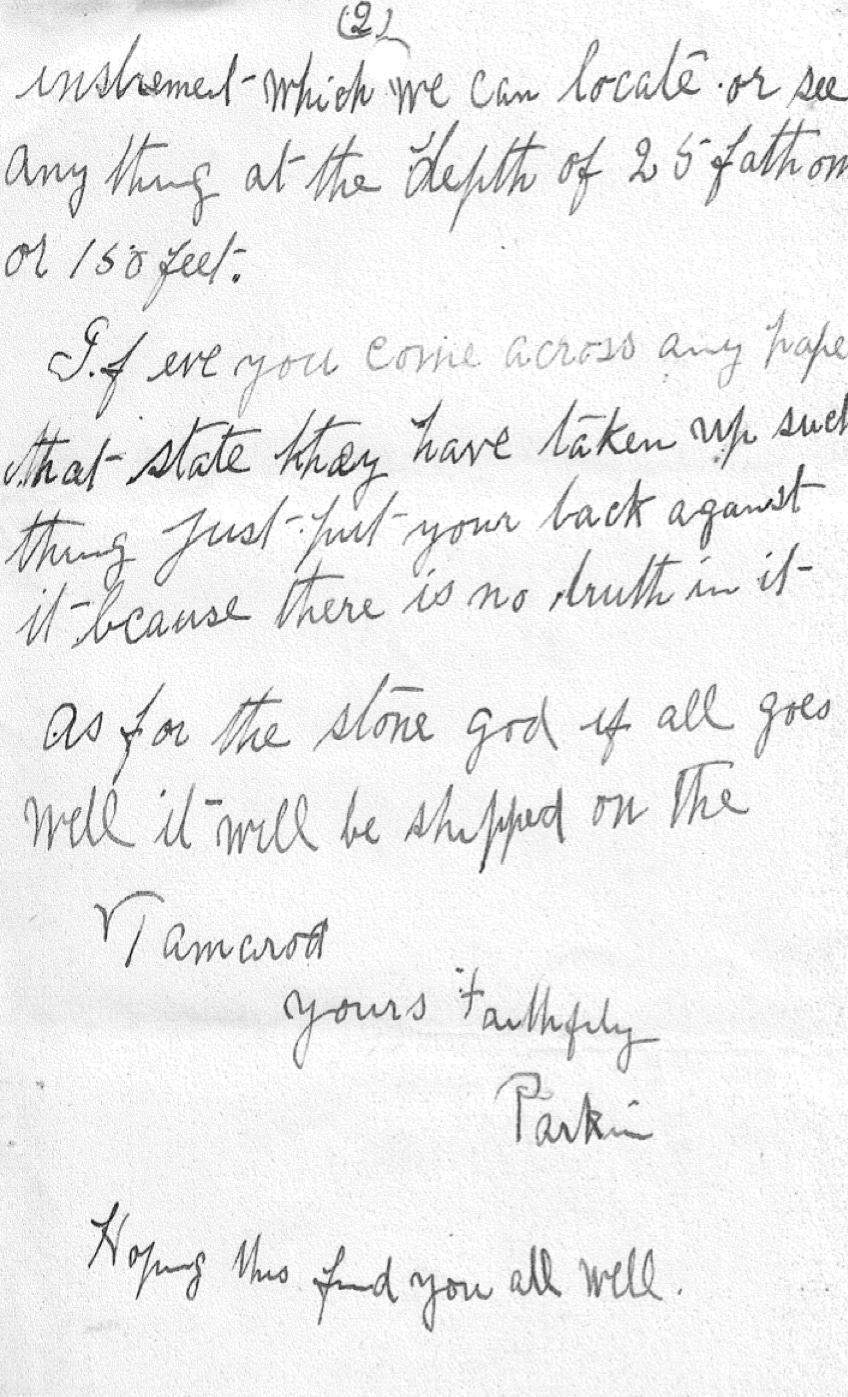

A Clue Emerges: At this point, I turned to Moira White, our Curator of Humanities, who dived into the museum’s archives. Her initial research was a bit disappointing: She uncovered a letter from W.R.B. Oliver, a 1930s director of the Dominion Museum (now Te Papa), vaguely referencing a note from a Parkin Christian.

Letter from Director of Dominion Museum to Director of Otago Museum, March 8th 1935

Sadly, Parkin’s letter was missing. This was museum-world intrigue at its finest: letters without attachments, artefacts with murky origins, and a faint whiff of bureaucratic disdain wafting through the decades.

But who was Parkin Christian? And why was he offering bits of the Bounty to a museum in New Zealand? Was it simply a casual “Oh, here’s some shipwreck material you might want” situation? And why didn’t the Dominion Museum want it? The plot thickened.

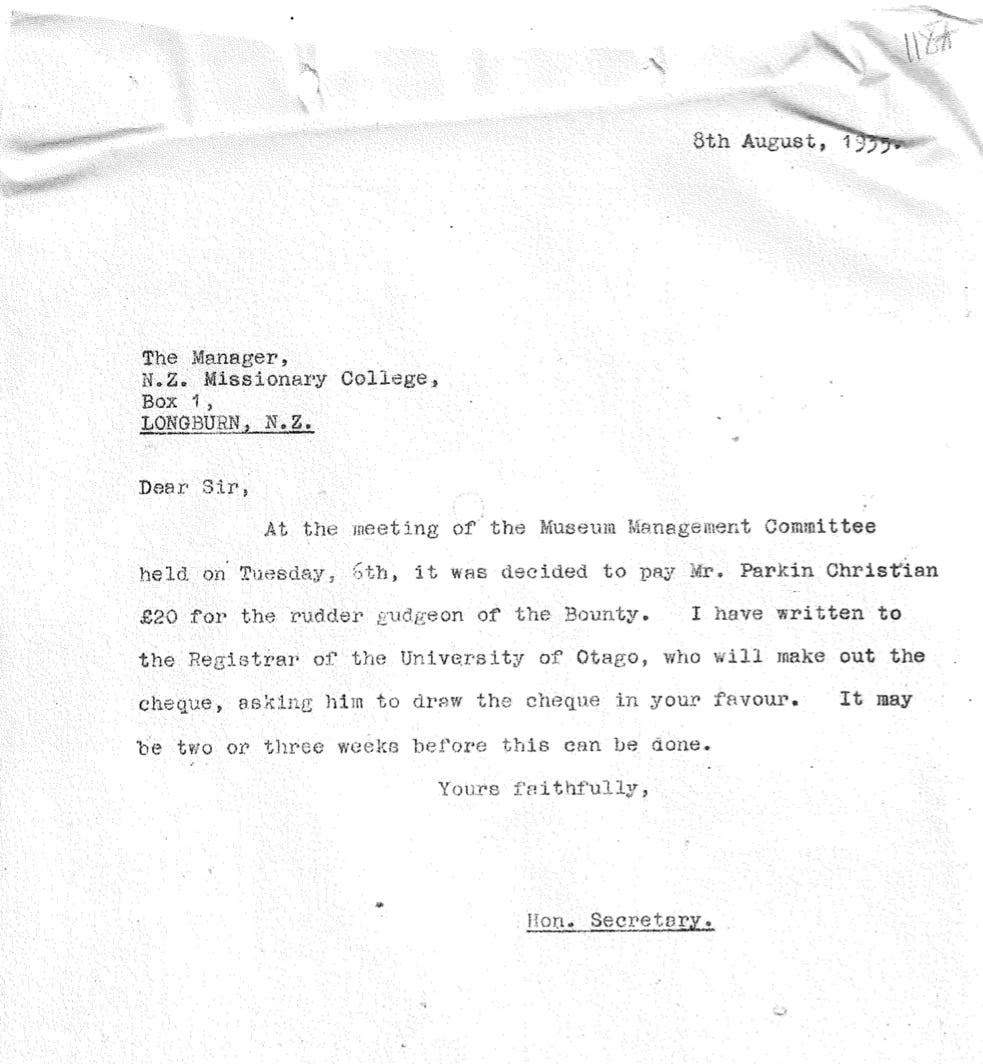

A Break in the Case: After more digging, Moira unearthed a letter from our archives that cracked things wide open. Dated 8th August 1935, it was from H.D. Skinner, Otago Museum’s then-director, to the New Zealand Missionary College. Skinner casually mentioned sending £20—not to Parkin Christian, mind you, but to the college. Why, exactly, were we paying a school for ship relics?

Letter from HD Skinner to NZ Missionary College, August 1935

At this point, I turned to Google, the modern museum detective’s best friend. A quick search for “Parkin Christian” led me to the Pitcairn Island Study Centre, whose Director, Herb Ford, was a veritable fountain of knowledge.

Secondly, on a hunch, I wrote to the archivists at each of the other major Museums in New Zealand to see if they could help with a more complete copy of the original correspondence from WRB Oliver (I assumed that a copy of Parkin's letter would have been sent to both Auckland and Canterbury Museums as well as Otago, so I emailed Te Papa, Auckland and Canterbury to see if they could help).

Parkin Christian

My research revealed that Charles Richard Parkin Christian was a prominent resident of Pitcairn. He was born on November 27th 1883, as the third of nine children. His Parents were Francis Hickson Christian and Eunice Jane Lawrence Young. Parkin himself married Rosalind Eliza Butler, and together they had three children: a daughter, Lorena (born in 1910 but who died a few days after birth), another daughter, Marjorie, born in 1912, and a third child, their son Richard, born in 1915 (remember Richard as he becomes a key player in the story later!)

Parkin was an important member of the Pitcairn Community, serving as coxswain of one of the Island boats for many years and eight terms as Island Magistrate (equivalent to Mayor of the Island).

However I became much more interested when my research revealed Parkin Christian to be the person who, in the early 1930s, found and recovered the rudder from the Bounty, which had been on the ocean floor in Bounty Bay since the ship was burned and sunk by the mutineers.

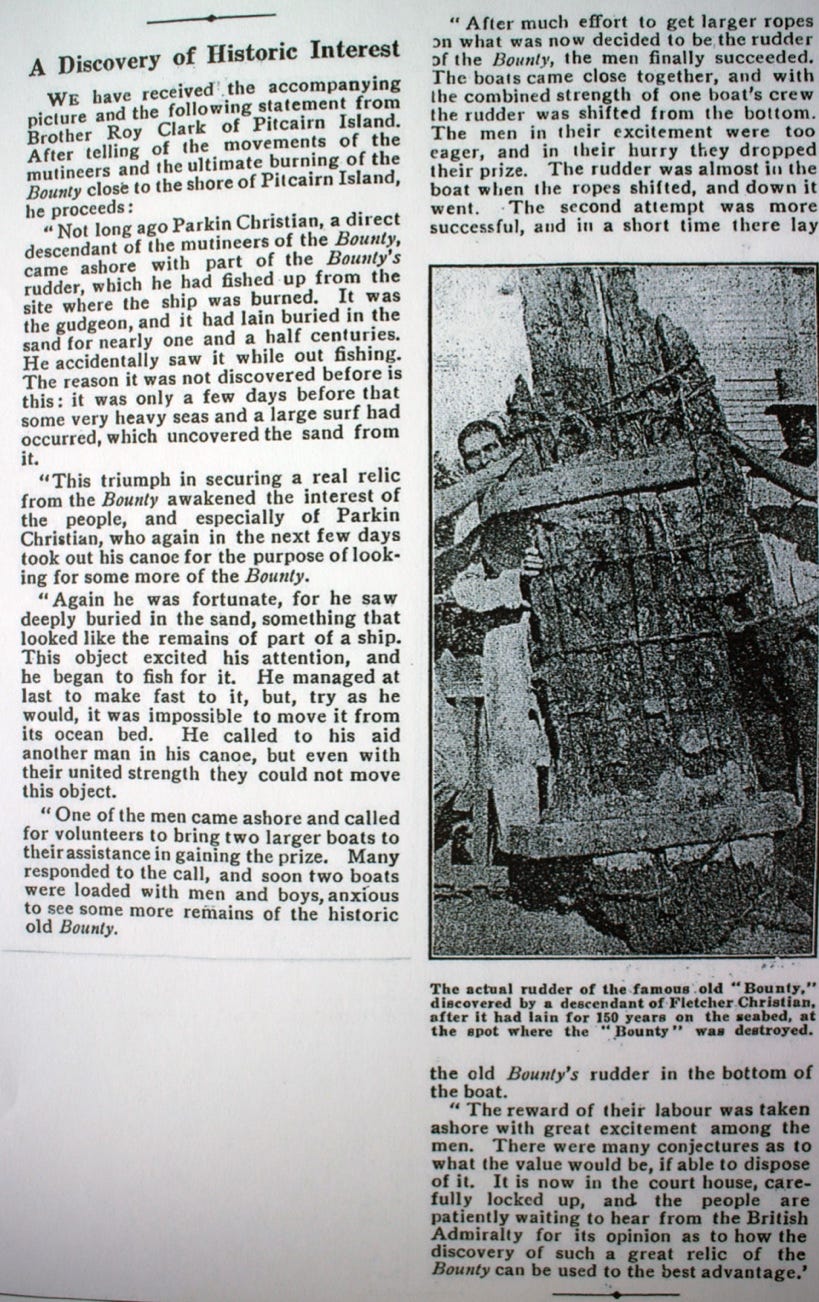

Herb Ford provided me with a copy of an article from the Australasian Record of the Australian Division of the Seventh Day Adventist faith, dated May 28th, 1934, that tells the story of the rudder's recovery.

Page 3 of Australasian Record, May 28th 1934

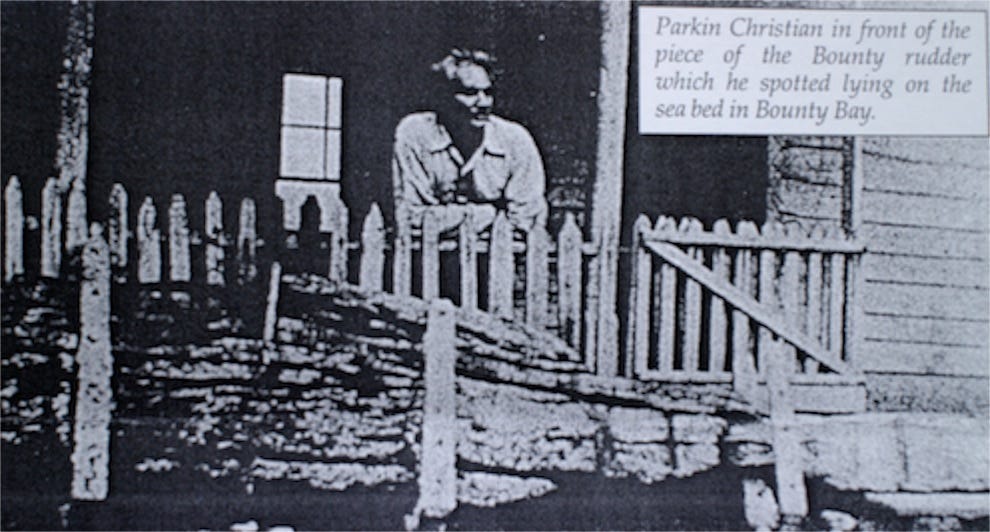

Interestingly, the large rudder shown in the article is now displayed in the Fiji Museum in Suva. Maurice Allward's article in the second edition of the Pitcairn Postcard Magazine (copy supplied by Herb Ford) explains the reasons for its presence in Fiji in detail. The article includes pictures of the rudder outside Parkin Christian's house.

Parkin Christian with rudder remnant outside his house

So, to summarize: Parkin was a prominent Pitcairner, descended from none other than Fletcher Christian himself. In the 1930s, Parkin had recovered pieces of the Bounty’s rudder from Bounty Bay using what can only be described as DIY scuba gear. The rudder fragments became a hot commodity among visitors to the island, who snagged souvenirs like they were at a nautical yard sale.

The larger piece of the rudder eventually made its way to the Fiji Museum (in exchange for, I kid you not, a first-class radio).

Remaining parts of Bounty Rudder on display at Fiji Museum

So we now know that Parkin Christian recovered various parts of the rudder, and the main part is now on display in Fiji. But we still need to find out why, in 1935, Parkin decided to hawk around the pintle and gudgeon to Museums in New Zealand.

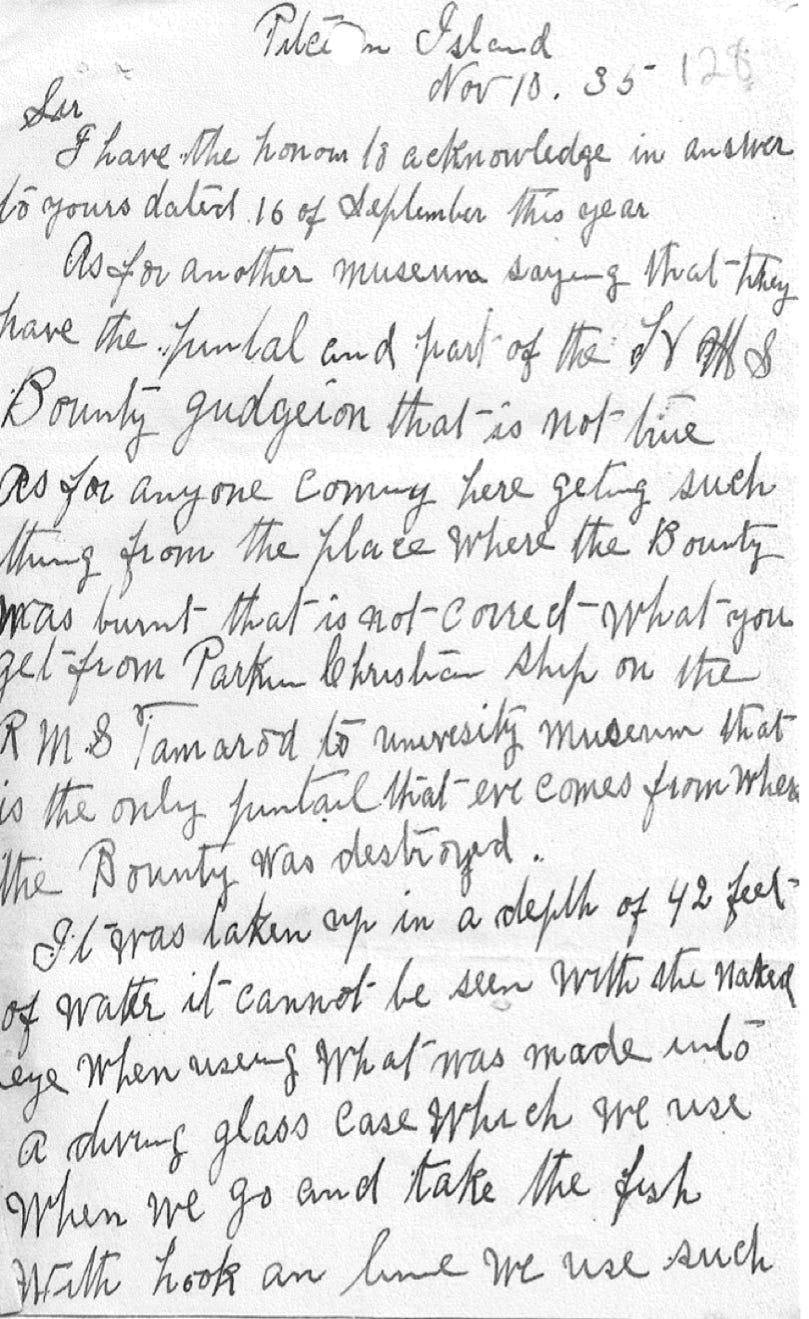

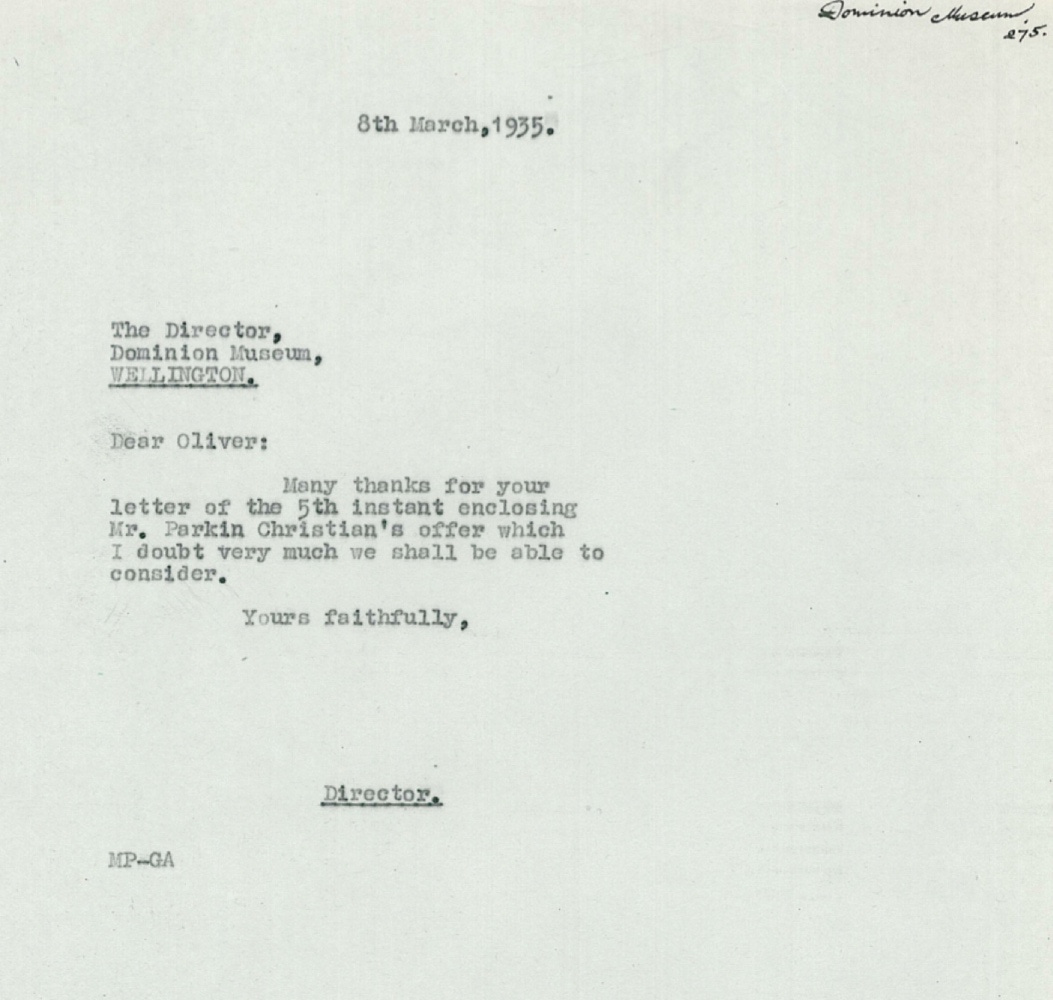

Further research into our records at the Otago Museum uncovered two letters from Parkin to H.D. Skinner, both dated November 10th 1935. The first is particularly important because it gives a first-hand description of the circumstances of the rudder's discovery, which Parkin states was in October 1933. The letter, which is beautifully written also speaks to the fact that these are artefacts from the Bounty, and notes that while other Museum's had asked for them, only Skinner offered any money for them!

Page 1 of letter from Parkin Christian to HD Skinner, November 10th 1935

Page 2 of letter from Parkin Christian to HD Skinner, November 10th 1935

On the same day that Parkin wrote the above letter, he wrote a second letter, presumably in response to another letter he had received from Skinner seeking assurance about the provenance of the pintle and gudgeon. In this second letter, Christian again describes the circumstances of the rudder's discovery and recovery; in this letter, Christian states that.

"it was taken up in a depth of 42 feet of water it cannot be seen with the naked eye when using what was made up into a diving glass case which we use when we go and take the fish with hook and line we use such instrument which we can locate or see anything at the depth of 25 fathom or 150 feet."

Christian seeks to reassure Skinner that the objects he has in the University Museum are from the Bounty;

Parkin states, "if ever you come across any paper that states they have taken up such thing, just you back against it because there is no truth in it."

Page 1 of the second letter from Christian to Skinner, November 1935

Page 2 of Second Letter from Christian to Skinner, November 1935

We now know that Parkin Christian discovered and recovered the Rudder from HMS Bounty in October 1933, following a storm that moved some sand that had previously been covering the wreckage. He found the rudder using a diving glass, a device that helped the Pitcairners see into the ocean when fishing.

But why did Parkin sell the pintle and gudgeon to a Museum in New Zealand?

This is where the second strand of my research also paid dividends.

Unfortunately, the archivist at Te Papa could find no record of the original correspondence between Christian and W. R. B. Oliver.

However, the Auckland Museum archivist found a copy of the correspondence, which completely unlocked the mystery.

Like us at the Otago Museum, they had received a letter from W R B Oliver.

Letter from Oliver to Director of Auckland Museum

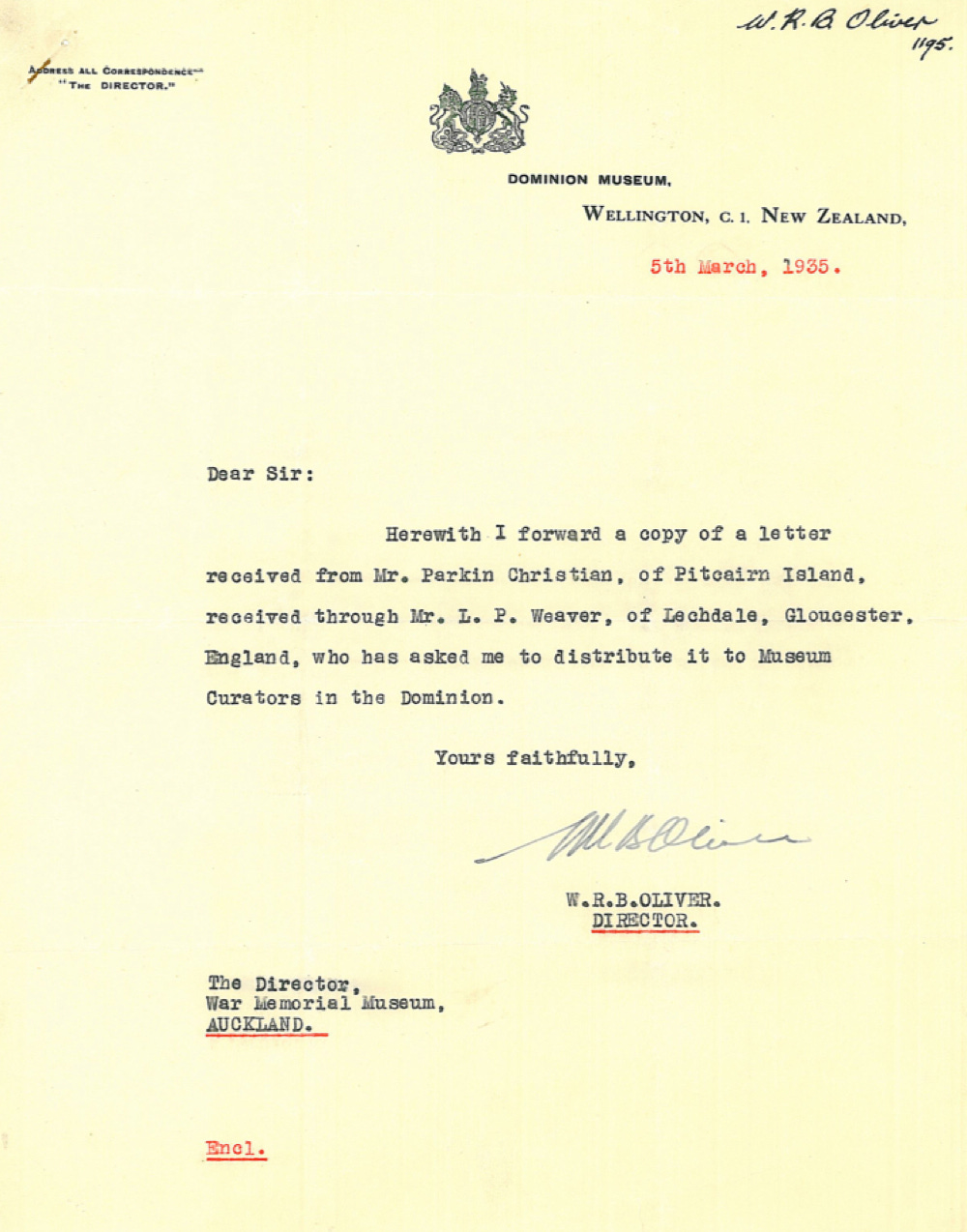

However, unlike the Otago Museum, Auckland had a copy of Parkin Christian's original letter, which explained why he was writing to museums in New Zealand.

The original letter from Parkin Christian to the Director of the Dominion Museum Wellington, November 13th 1934

It turns out that in the early 1930s, Parkin's son Richard was studying at the NZ Missionary College, and Parkin didn't have enough money to see his son through college. So, the Bounty's Pintle and Gudgeon were offered for sale to museums in New Zealand in the hope that one would be prepared to pay.

This is why The Otago Museum sent a cheque to the NZ Missionary College, and it also explains why the Otago Museum has artefacts from the Bounty. Parkin's second letter to HD Skinner in November 1935 also explains why The Otago Museum has a Moai, since Parkin mentions in the last paragraph that "as for the stone god, if all goes well it will be shipped on the Tamaroa" Skinner had obviously asked if Christian had any other objects of interest during the correspondence about the purchase of the gudgeon and pintle. Herb Ford has noted that Tamaroa was a frequent caller at Pitcairn in the 1930s. He recorded her often in his book (second edition) "Pitcairn Island as a Port of Call" (McFarland), in which he lists every ship (with particulars about each call) that called at Pitcairn from the arrival of the Bounty in 1790 to 2011.

Incidentally, it is fascinating that while HD Skinner in Otago jumped at the chance to purchase these objects, both the Dominion Museum and the Auckland Museum rejected the idea of purchasing the Pintle and Gudgeon; the letter from the Director of the Auckland Museum to the Director of the Dominion Museum shows very little interest in the objects.

Letter from Director of Auckland Museum to Director Dominion Museum March 8th 1935

So… there you have it. The Otago Museum has the pintle and gudgeon from HMS Bounty because Parkin Christian's son was studying at Missionary College in New Zealand. Parkin was running out of money (like many other parents of college students worldwide!) Couple this with H.D. Skinner, a highly entrepreneurial Director of the Otago Museum at the time who could see the historical value of the objects. At the same time, the other Directors of Museums in New Zealand couldn't, and you get a set of circumstances where key objects from Pitcairn's history end up in the collection of the Otago Museum.

Why any of this matters: This whole saga—the letters, the pintle, the gudgeon, the tuition payment—illustrates exactly why I love working in museums. Every object has a story, and sometimes those stories are delightfully tangled. They involve shipwrecks, mutinies, desperate parents, and museum directors who saw value where others didn’t. It’s like being part historian, part detective, and part treasure hunter. And while I may never fully understand why someone rejected the pintle of a legendary ship, I’m grateful Otago Museum didn’t.

I'd like to thank Moira White from the Otago Museum and Herb Ford, Director of the Pitcairn Islands Study Centre, for helping me put together this blog. I'd also like to thank the archivists at Te Papa, the Auckland War Memorial Museum, and the Director of the Canterbury Museum for their help in my research.

Postscript:

in July 2019, I visited Pitcairn en route to trying to observe a total solar eclipse on Oeno Island. Unfortunately, it was cloudy during the eclipse, and I saw nothing. However, I did get to spend a couple of days on Pitcairn and even got to visit the Pitcairn Museum and the (overgrown) site of Parkin’s house! I recorded the video at the start of this post during the farewell ceremony when the island’s inhabitants sang a song to wish us well. I may have only visited Pitcairn for two short days, but the memories will live with me forever.

Anchor of HMS Bounty, Pitcairn Island, July 3rd 2019

![Oliver to Skinner[4] Oliver to Skinner[4]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!DLP1!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Ff9b57e97-15b2-464f-8ddf-468b7c051495_1240x1754.jpeg)

Share this post