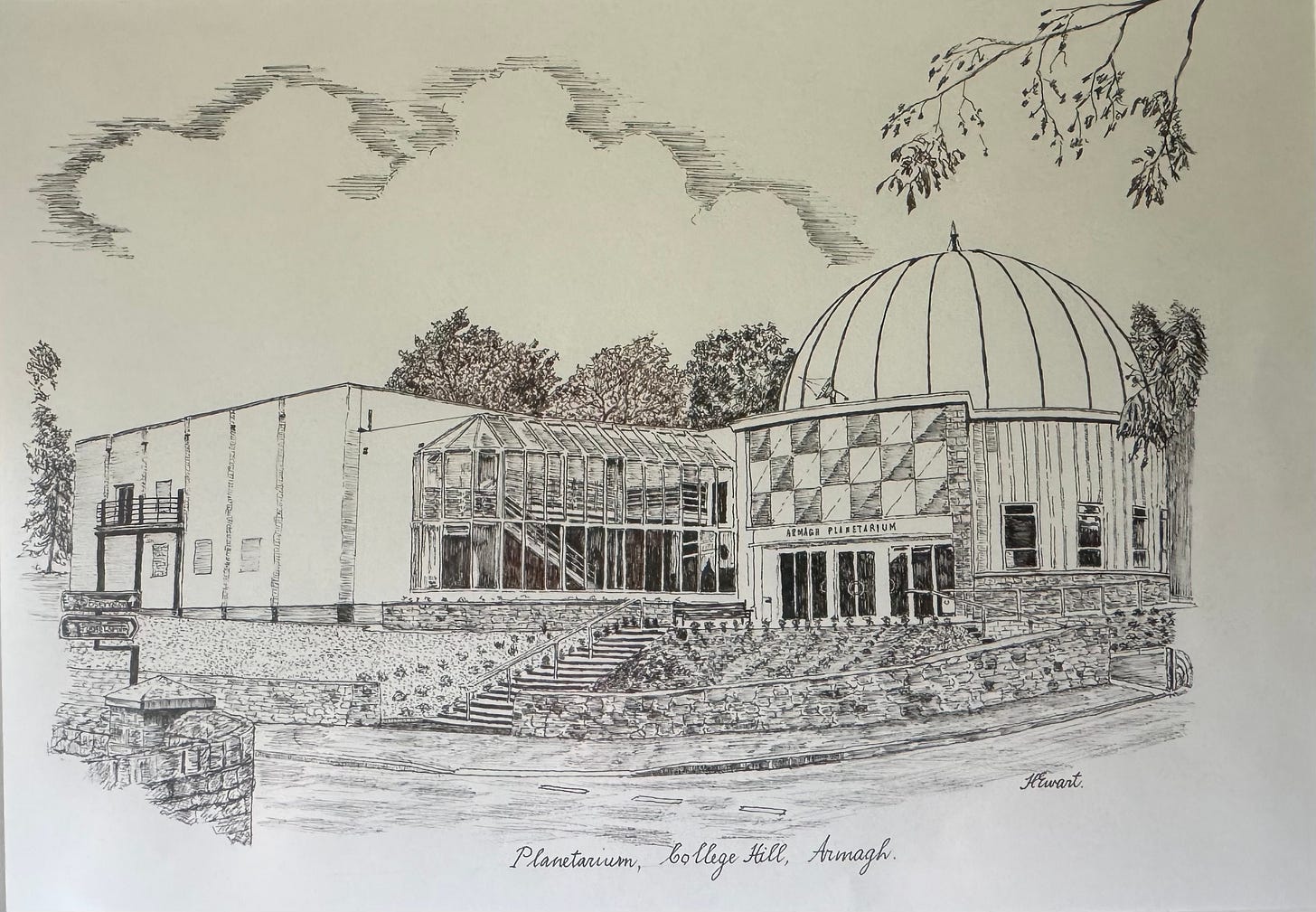

A original pen and ink sketch of the Planetarium in Armagh made by Hampton Ewart ( from my private collection)

It was 1991, and I was freshly installed as the Director of the Armagh Planetarium in Northern Ireland—a lofty title for a 24-year-old who’d just started shaving regularly. I had a PhD in astronomy, a head full of Big Ideas, and the kind of confidence that only comes from knowing absolutely nothing about the real world. I was, in short, insufferable.

One afternoon, I was at the front desk, feigning authority and trying not to look like a kid who’d accidentally wandered into someone else’s job, when a woman stormed up to me. She had the look of someone who’d been wronged—possibly by the universe itself, but more likely by me.

“I’ve just been insulted by one of your exhibits,” she declared, her voice sharp enough to leave marks.

This wasn’t in the management manual. I blinked at her, momentarily at a loss. “I’m sorry?”

She repeated herself, this time louder, in case the planets on the ceiling were hard of hearing. “Insulted. By an exhibit.”

“Oh,” I said, trying to summon my inner diplomat. “Which one?”

She jabbed a finger toward the gallery, and my heart sank. I knew instantly which exhibit she meant.

The I Speak Your Weight scales were my pride and joy, a triumph of early ’90s computer programming and, I liked to think, a stroke of scientific genius. Each planet had its own scale, and when you stepped on, the computer—using a voice that sounded suspiciously like Stephen Hawking after a bad night—would announce your weight on that planet. It was educational, interactive, and, I thought, quite fun.

What I hadn’t accounted for was schoolchildren. The day before, a group of them had discovered that if they piled onto the scales in teams of four or five, the computer would spout ridiculous numbers—“Your weight on Jupiter is 600 kilograms!”—and chaos would ensue.

So, in a fit of exasperated brilliance, I reprogrammed the scales to deliver a new message whenever the (Earth) weight exceeded 150 kilograms: “One at a time, please.”

I hadn’t considered that this could be, let’s say, socially sensitive.

The woman glared at me, her cheeks as red as Mars. “I stepped on your Jupiter scale,” she hissed, “and it told me to get off.”

There are moments in life when you realize you’ve made a terrible mistake, and then there are moments when you know you’ve made a terrible mistake and will have to explain it to an angry stranger. This was the latter.

I stammered something about group weights and calibration, but it was no use. She wasn’t interested in the science of planetary mass; she wanted blood—specifically, mine.

Ultimately, I apologized profusely, promised to reprogram the exhibit, and threw in a free planetarium show for good measure. She left mollified, though not before shooting me a look that said she’d be telling this story at every dinner party for the rest of her life.

As for me, I spent the rest of the day dismantling my beloved scales and wondering if maybe, just maybe, the universe had made a mistake by giving me this job.