During the national lockdown here in New Zealand which began in March 2020, I began looking for something to distract me from thinking about COVID. I stumbled upon an article about pinhole photography. This is perhaps the most basic form of photography, involving little more than a container with a hole in it exposing a piece of photographic film or paper. No lenses are required, but the exposure time needed to record a decent image can be minutes rather than seconds. Once I built my first pinhole camera and took and developed the first picture, I became obsessed with this simple form of photography. Although not perfectly sharp, pinhole photographs have a beautiful eerie quality I find absolutely intriguing.

Since I’m not very skilled with my hands, my first pinhole camera quickly fell apart I was therefore overjoyed to find that some beautiful hand-crafted cameras are sold online. By the time lockdown was over, I had persuaded my better half to allow me to “re-purpose” our laundry as a darkroom and I was taking images during my morning commute down the Otago Peninsula and on my travels across New Zealand.

Of course, it wasn’t long before I sought to marry my newfound photographic infatuation with my lifelong passion for astronomy. On 1st October 2020, I set up a small commercial pinhole camera (made by Solarcan www.solarcan.co.uk ) on the deck of my home in Portobello (Latitude 45.84S Longitude 170.64E).

My aim was to record the apparent motion of the sun across the sky from just after the southern hemisphere spring equinox in September 2020 right up to the winter solstice in June 2021. For this first attempt, I decided to point the camera roughly west so I could record the changing position of the sunset.

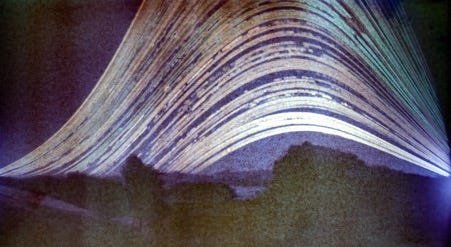

This image is in fact a solargraph. The pinhole camera’s curved focal plane contained photosensitive photographic paper which was chemically darkened by sunlight during the long exposure. This formed a negative image which was scanned on a digital scanner.

The exposure time (using iso2 photographic paper with an f/132 pinhole), was 262 days, or just under nine months. In addition to showing the changing position of sunset, it illustrates cloud cover and how the sun’s altitude changes at noon during the year. Unfortunately, I didn’t position the camera quite right and didn’t capture the noon summer sun as it moved out of frame.

My next experiment began on the summer solstice (21 December 2020) and ended on the winter solstice (21 June 2021) for an exposure time of 182 days. This time I mounted the pinhole camera pointing North in my garden and angled it at 45 degrees. The exposure successfully captured the full range of solar motion and is also a fascinating record of how cloudy it was during the six-month exposure.

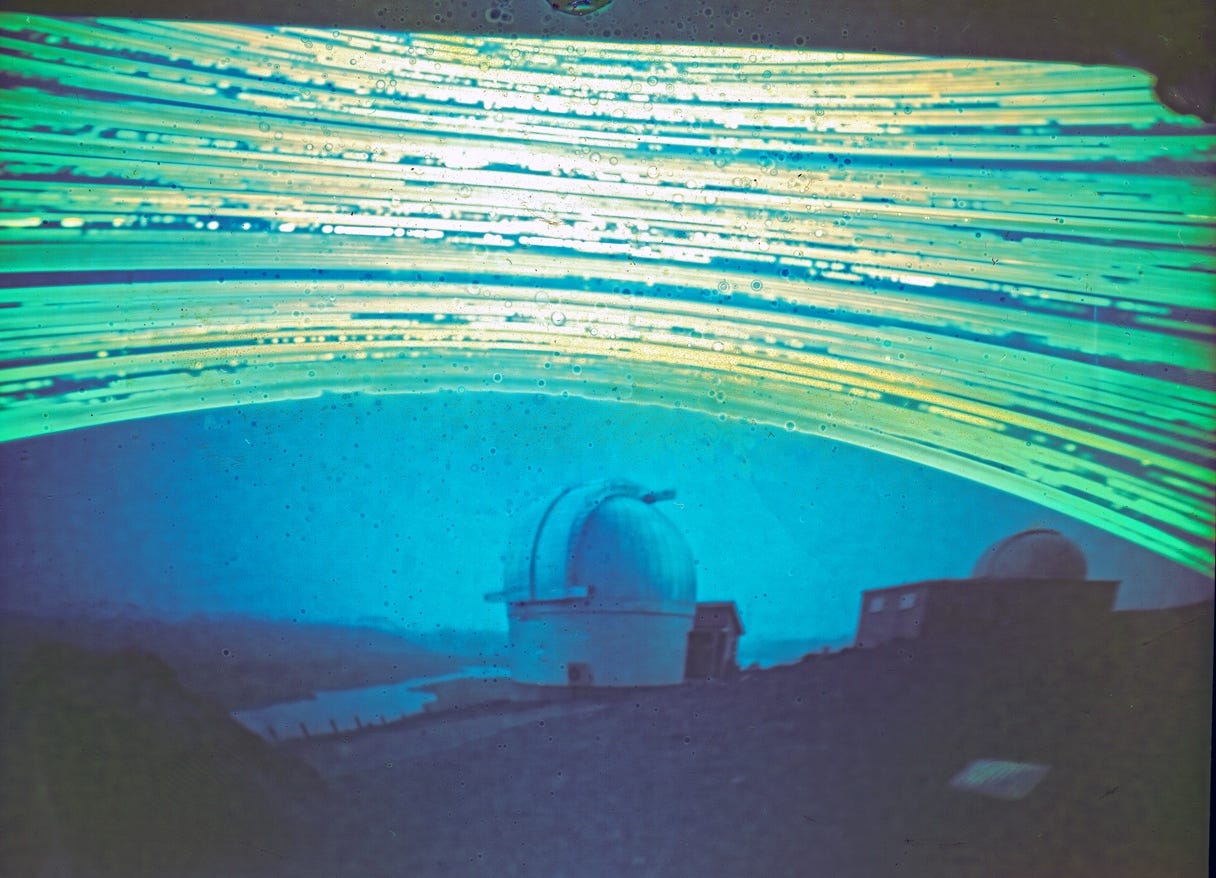

With several successful images “in the can” I decided to become more creative. During an observing run on the 0.6M telescope at the University of Canterbury’s Mount John Observatory in January 2021 I was given permission to position a camera on a North facing wall. I recovered the camera during another observing run in July 2021. The resulting 195-day exposure successfully recorded the apparent motion of the sun over telescope domes atop Mount John looking towards Lake Alexandrina. If you compare it to the images from Portobello the image also beautifully illustrates the difference in cloudiness between the Mackenzie basin and the east coast of the South Island!

Delighted by the results of my first experiments in long exposure pinhole photography I pondered what wonders I could capture with a really old camera from my collection. The Graflex Speed Graphic Press camera uses 5-inch by 4-inch glass plates, which, believe it or not, can still be purchased online!

Just after the winter solstice in June 2021, I set up the camera. After carefully focussing it on infinity using a loupe. I then made a 4-hour exposure of the sun setting behind Pudding Island. I repeated the exercise on 23rd September, and 22 December, the dates of spring equinox and summer solstice. I scanned the resulting images and, using photoshop, aligned them to create a panoramic image.

I find it fascinating to see how much sunset has moved southwards along the horizon between solstice and equinox. It is also possible to see how the sun’s path is steeper near the equinox than at the summer and winter solstices which is, of course, why twilight is shortest in March and September.

Glass plate photography is definitely not for the fainthearted. However one of the benefits of this type of photography is being able to sit in the dark room with a safe light switched on watching the image develop right before your eyes.

Long exposure photography of the type I have described above is a very hands-off process. You mount the camera and basically leave it alone for months on end. The final analogue project I shall describe was very different in nature. It was much more hands on, and would require me to open and close the shutter of a pinhole camera at the same time every day for an entire year.

I mounted an Ilford Obscura f/248 pinhole camera facing West. Inside the camera was a single ISO 2 rated 4x5 inch glass plate coated with light-sensitive silver halide emulsion. Beginning on 23rd September 2021, at 4pm precisely (5pm when summertime began), if the sun was visible in the sky, I opened the shutter for 20 seconds. At the winter solstice and autumn equinox, I opened the shutter for longer to record the apparent motion of the sun across the sky.

My project ended on 23rd September 2022. I dismounted the camera and took it to a makeshift darkroom in the laundry. Under red light, I removed the plate popping it into a chemical bath to develop the latent image. After a few minutes, I shouted with delight. My yearlong project to capture the solar analemma was successful!

The elongated figure of eight curve you can see is called a solar analemma. The shape you see depends on your location, the tilt of our planet’s axis and Earth’s varying speed around the sun. Thanks to Earth’s 23.5-degree axial tilt in relation to its orbit, the sun’s altitude and rate of motion in the sky change during the year. Also, because our home planet’s orbit is elliptical, its velocity changes as we go around the sun. We move fastest in January when closest and slowest in July when furthest away. Earth’s ever-changing speed is also a factor which affects the sun’s observed position.

A detailed explanation of the analemma won’t be given here. It was fully explained in the excellent article by Ashley Marles in the September 2020 edition of Southern Stars. The article also presented a fine analemma that the author had recorded using a digital technique.

Undoubtedly modern digital imaging techniques have revolutionised our ability to study the cosmos. However, as I hope this short article has shown, some of the oldest and simplest analogue photographic techniques still have a lot to offer to those patient and dedicated souls who wish to record the motions of the heavens for themselves.